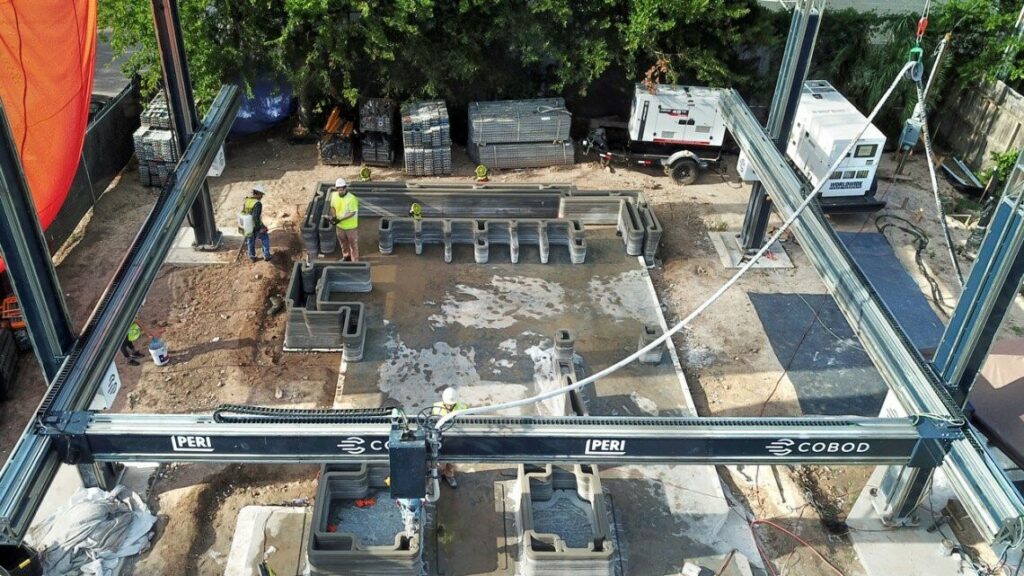

Cornell University researchers are constructing 3D-printed homes using blends of concrete and wood to reduce waste and cost. Their first-of-its-kind hybrid design connects structural elements composed of 3D-printed concrete with conventional wood framing representative of most U.S. residential construction. The combination shows how each material can be used where it works best, with minimal waste, to create buildings that are efficient, resilient against increasingly intense weather events and potentially more affordable.

The house is being built in partnership with PERI 3D Construction, which has completed six 3D-printed structures in the U.S. and Europe; Houston-based engineering and design-build contractor CIVE; and other building industry partners.

Designers Leslie Lok and Sasa Zivkovic, assistant professors of architecture in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning (AAP) and co-principals of the HANNAH Design Office, say the two-story, single-family home is demonstrating innovative construction processes that can be scaled up to multifamily and mixed-use developments, helping to address housing shortages.

“Our hybrid construction approach creates a building system that is structurally efficient, easily replicable and materially responsive,” Lok said. “The project also highlights the exciting design potential of mass-customized architectural components to meet homeowners’ needs and to simplify building system integration.”

The 4,000-square foot Houston project advances that work to a larger scale, one that will require another U.S. “first” – a relocation of the large gantry supporting the printer, measuring roughly 60 feet long, 30 feet wide and 30 feet tall, to complete the structure.

The building features;

- The three-bedroom, three-bathroom

- A two-car garage

- 40-foot chimney

- Design and construction processes well-suited to multifamily developments

“These design efforts aim to increase the impact, applicability, sustainability and cost-efficiency of 3D printing for future residential and multifamily buildings in the U.S.” added Zivkovic.

The designers said their approach could also accelerate construction timelines and reduce costs, since concrete printers may be operated by as few as three or four people. It also minimizes waste, as material can be mixed on demand and printed only for structurally important sections, and can more efficiently integrate wood framing in a modular design.

“Apart from printing technology, the integration of printing with building design and building materials, and the streamlining of construction process are important aspects in the realization of such a project,” Zivkovic said. “We are using this project to demonstrate how 3D printing is not only market-ready, but also capable of building well-designed and high-performance architecture.”

Apart from printing technology, the integration of printing with building design and building materials, and the streamlining of construction process are important aspects in the realization of such a project,” Zivkovic said. “We are using this project to demonstrate how 3D printing is not only market-ready, but also capable of building well-designed and high-performance architecture.”

For the Houston home, the printed material is locally sourced and uses cement with a reduced carbon footprint, a mix that may include fly ash, slag and other industrial byproducts. The designers are collaborating with colleagues in the College of Engineering on research relating to ecofriendly building materials, including the potential for concrete to store methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Wood framing, meanwhile, is a renewable resource but is often a product of forest monocultures and may be transported over long distances. Lok and Zivkovic said the Houston home optimizes use of both materials while taking better advantage of their design potential than many structures limited to only one of them.