Most people never think about what happens between a biopsy and a diagnosis.

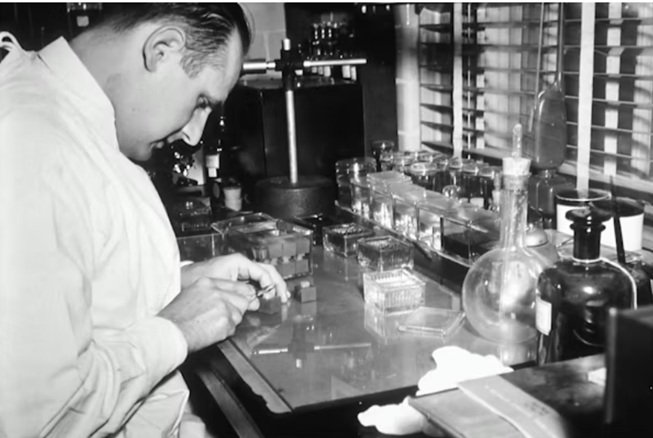

A doctor takes a small piece of tissue. A pathologist eventually looks at it under a microscope and tells you what’s going on.

Simple, right?

Not even close.

Between those two moments is an entire chain of precise, painstaking laboratory work that most patients and even many medical professionals outside the lab never see.

Tissue doesn’t just go from body to microscope. It gets fixed, processed, embedded, sectioned, stained, and mounted before anyone can make sense of it.

Each step matters. Skip one or do it poorly and the final slide is useless.

I find this fascinating. Not just the science, but the craft of it. Because that’s really what histology is. Part science, part craft. The people doing this work are incredibly skilled and the tools they rely on are more specialised than most people realise.

Let’s pull back the curtain on what actually happens in a histology lab.

Why Tissue Preparation Is Such a Big Deal

Here’s the core problem. Living tissue is soft, wet, and fragile. You can’t just slice it open and look at it.

To study cells properly, you need thin sections. Incredibly thin. We’re talking a few micrometres thick. That’s thinner than a human hair by a long way.

Getting tissue to that point requires turning it from something soft and pliable into something firm enough to be cut with extreme precision.

That’s the whole game in histology. Taking delicate biological material and preparing it so it can be examined at the cellular level without distorting or destroying what you’re trying to see.

If the preparation is sloppy, everything downstream falls apart. The pathologist can’t read a bad slide. A diagnosis gets delayed or, worse, gets made on compromised information.

The stakes are quietly enormous.

The Journey From Tissue to Slide

Let’s walk through the main stages. Each one builds on the last.

Fixation comes first. The tissue gets placed in a chemical solution (usually formalin) that preserves its structure and stops it from breaking down.

Think of it like pressing pause on decomposition. The cells stay in place, the proteins get locked, and the tissue holds its shape.

Timing matters here. Too little fixation and the tissue is still too soft. Too much and it becomes brittle and hard to work with.

Processing is next. The water in the tissue gets gradually replaced with a medium that will support it during cutting. This usually involves passing the tissue through a series of chemical baths: alcohol for dehydration, a clearing agent, and finally melted paraffin wax.

The tissue ends up embedded in a solid block of wax. It looks like a small, pale rectangle. Nothing dramatic. But inside that block is a perfectly preserved piece of biological material ready for the next critical step.

Embedding sounds simple but takes real skill. The tissue needs to be oriented correctly inside the wax block. If it’s tilted, angled wrong, or positioned poorly, the sections cut from it won’t show the structures the pathologist needs to see.

A good embedding job is invisible. You only notice it when it’s done badly.

The Cut That Makes Everything Possible

This is where things get really interesting.

Once the tissue is locked in its wax block, it needs to be sliced into sections thin enough for light to pass through. That’s the only way to examine it under a microscope.

The instrument that does this is called a microtome. It’s essentially a precision cutting device that shaves incredibly thin ribbons of tissue from the wax block.

We’re talking sections that are typically four to five micrometres thick. For perspective, a sheet of standard printer paper is about 100 micrometres. So these sections are roughly twenty times thinner than paper.

Getting a clean, consistent section at that thickness is no small feat.

The blade has to be perfectly sharp. The block has to be properly trimmed and oriented. The temperature of the wax matters. Even the angle of approach makes a difference.

Experienced histotechnologists make it look effortless. They’ll produce ribbon after ribbon of perfect sections, floating them onto a warm water bath and picking them up on glass slides with a smoothness that comes from doing it thousands of times.

But watch a beginner try it and you’ll quickly see how much skill is involved. Torn sections. Uneven thickness. Ribbons that curl, crumble, or refuse to cooperate.

It’s one of those tasks where the gap between “adequate” and “excellent” is enormous, and it shows up directly in the quality of the final slide.

Staining: Making the Invisible Visible

Once the section is on the slide, it’s essentially transparent. You can’t see much of anything without help.

That’s where staining comes in.

Chemical stains bind to different components of the tissue and give them colour. The most common combination is haematoxylin and eosin, often shortened to H&E. Haematoxylin stains cell nuclei a deep blue or purple. Eosin stains the surrounding structures pink.

The result is a beautifully detailed, colour coded map of the tissue’s architecture.

A well stained slide is genuinely beautiful, even if you don’t know what you’re looking at. The contrast between the blue nuclei and the pink cytoplasm reveals patterns, structures, and abnormalities that would be completely invisible otherwise.

But H&E is just the starting point. There are dozens of special stains, each designed to highlight specific tissue components.

Need to see collagen? There’s a stain for that. Mucin? Iron deposits? Nerve fibres? Fungi? Each one has its own protocol, its own chemistry, and its own quirks.

Immunohistochemistry takes things even further, using antibodies to detect specific proteins in the tissue. It’s become essential for modern cancer diagnosis, helping pathologists identify exactly what type of tumour they’re dealing with.

The Human Factor

Something that gets lost in discussions about lab work is how much of it still depends on human skill and judgment.

Yes, automation has transformed parts of the process. Tissue processors run overnight. Automated stainers handle high volumes with impressive consistency.

But the critical decision points? Those are still human.

Choosing how to orient a specimen. Deciding where to cut. Evaluating whether a section is good enough or needs to be redone. Troubleshooting when something doesn’t look right.

These judgments require training, experience, and a kind of intuitive understanding that comes from working with tissue day after day.

I’ve spoken with histotechnologists who can glance at a section and tell you instantly if something went wrong during processing. They can feel the difference in a wax block that wasn’t properly infiltrated. They know by the way a ribbon behaves whether the blade needs changing.

That kind of expertise takes time to build. And it’s irreplaceable.

Why Equipment Quality Matters So Much

This is something that might seem obvious, but it’s worth saying directly.

In a field where precision is measured in micrometres, the quality of your equipment isn’t nice to have. It’s fundamental.

A dull blade doesn’t just produce bad sections. It can introduce artefacts that mimic pathology, leading to potential misinterpretation.

A poorly calibrated instrument doesn’t just slow you down. It produces inconsistent results that undermine everything that follows.

Labs that invest in reliable, well maintained equipment produce better work. Full stop.

This applies across the board. From the fixation stage right through to the microscope. Every piece in the chain matters.

But it’s especially true for the cutting stage, because that’s where precision is most critical and where small equipment issues create the biggest downstream problems.

The Bigger Picture

Here’s what I think most people miss about laboratory work in general.

It’s invisible. Deliberately so.

When it’s done well, nobody notices. The slide is perfect. The diagnosis is clear. The patient gets their answer.

Nobody calls the lab to say “great embedding job on that specimen.” Nobody sends a thank you note for a beautifully cut section.

But the work matters enormously. Every slide that goes under a microscope represents a chain of decisions, skills, and precision steps that have to go right.

Behind every diagnosis is a person who fixed that tissue properly. Someone who embedded it with care. Someone who cut it with skill. Someone who stained it with attention to protocol.

These aren’t glamorous roles. You won’t see histotechnologists on magazine covers. But the healthcare system literally could not function without them.

What This Means If You’re Interested in the Field

If any of this has sparked your curiosity, histology is a genuinely rewarding field to explore.

It combines hands-on technical work with meaningful outcomes. You’re not doing abstract tasks. Every sample you process belongs to a real person waiting for real answers.

The learning curve is steep. Mastering tissue sectioning alone can take months of practice. But the people who stick with it tend to find deep satisfaction in the precision and craftsmanship involved.

It’s also a field with consistent demand. As long as medicine exists, tissue needs to be examined. And as diagnostic techniques become more sophisticated, the need for skilled laboratory professionals only grows.

Wrapping Up

Next time you hear about a biopsy result or a pathology report, spare a thought for what happened between the sample being taken and the diagnosis being delivered.

There’s an entire world of precise, skilled, largely invisible work behind that answer.

It involves chemistry, craftsmanship, expensive precision instruments, and people who have spent considerable time mastering techniques that most of us will never see.

And honestly? That’s one of the things I find most compelling about it.

The best work often happens where nobody is watching. In quiet labs, under bright lights, one perfect section at a time.